If you want to use a password manager (as you probably should), there are literally hundreds of them to choose from. And there are lots of reviews, weighing in features, usability and all other relevant factors to help you make an informed decision. Actually, almost all of them, with one factor suspiciously absent: security. How do you know whether you can trust the application with data as sensitive as your passwords?

Unfortunately, it’s really hard to see security or lack thereof. In fact, even tech publications struggle with this. They will talk about two-factor authentication support, even when discussing a local password manager where it is of very limited use. Or worse yet, they will fire up a debugger to check whether they can see any passwords in memory, completely disregarding the fact that somebody with debug rights can also install a simple key logger (meaning: game over for any password manager).

Judging security of a password manager is a very complex task, something that only experts in the field are capable of. The trouble: these experts usually work for competing products and badmouthing competition would make a bad impression. Luckily, this still leaves me. Actually, I’m not quite an expert, I merely know more than most. And I also work on competition, a password manager called PfP: Pain-free Passwords which I develop as a hobby. But today we’ll just ignore this.

So I want to go with you through some basic flaws which you might encounter in a local password manager. That’s a password manager where all data is stored on your computer rather than being uploaded to some server, a rather convenient feature if you want to take a quick look. Some technical understanding is required, but hopefully you will be able to apply the tricks shown here, particularly if you plan to write about a password manager.

Our guinea pig is a password manager called Password Depot, produced by the German company AceBit GmbH. What’s so special about Password Depot? Absolutely nothing, except for the fact that one of their users asked me for a favor. So I spent 30 minutes looking into it and noticed that they’ve done pretty much everything wrong that they could.

Note: The flaws discussed here have been reported to the company in February this year. The company assured that they take these very seriously but, to my knowledge, didn’t manage to address any of them so far.

Contents

Understanding data encryption

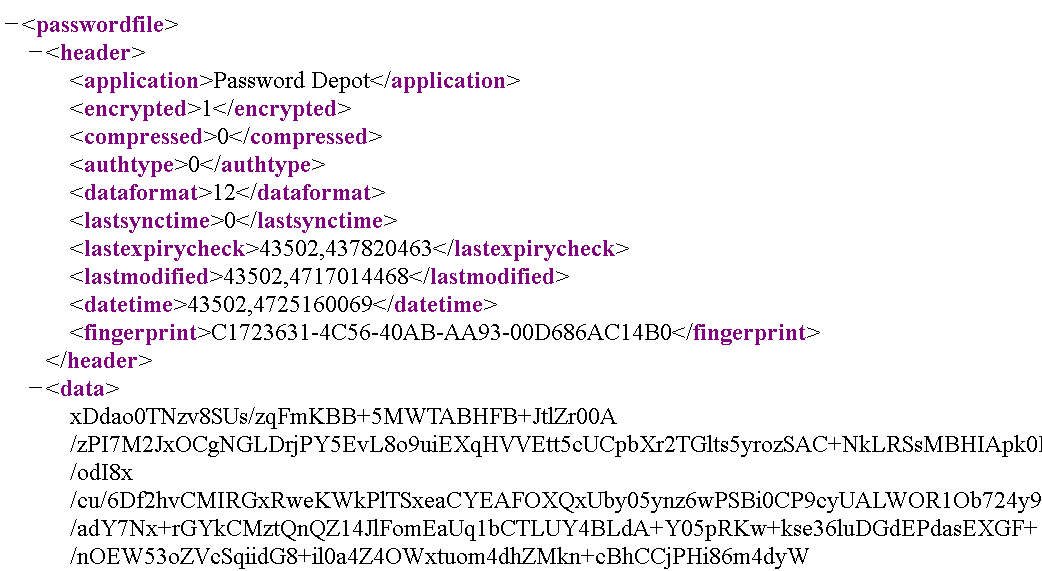

First let’s have a look at the data. Luckily for us, with a local password manager it shouldn’t be hard to find. Password Depot stores its in self-contained database files with the file extension .pswd or .pswe, the latter being merely a ZIP-compressed version of the former. XML format is being used here, meaning that the contents are easily readable:

The good news: <encrypted> flag here clearly indicates that the data is encrypted, as it should be. The bad news: this flag shouldn’t be necessary, as “safely encrypted” should be the only supported mode for a password manager. As long as some form of unencrypted database format is supported, there is a chance that an unwitting user will use it without knowing. Even a downgrade attack might be possible, an attacker replacing the passwords database by an unencrypted one when it’s still empty, thus making sure that any passwords added to the database later won’t be protected. I’m merely theorizing here, I don’t know whether Password Depot would ever write unencrypted data.

The actual data is more interesting. It’s a base64-encoded blob, when decoded it appears to be unstructured binary data. Size of the data is always a multiple of 16 bytes however. This matches the claim on the website that AES 256 is used for encryption, AES block size being 16 bytes (128 bits).

AES is considered secure, so all is good? Not quite, as there are various block cipher modes which could be used and not all of them are equally good. Which one is it here? I got a hint by saving the database as an outdated “mobile password database” file with the .pswx file extension:

Unlike with the newer format, here various fields are encrypted separately. What sticks out are two pairs of identical values. That’s something that should never happen, identical ciphertexts are always an indicator that something went terribly wrong. In addition, the shorter pair contains merely 16 bytes of data. This means that only a single AES block is stored here (the minimal possible amount of data), no initialization vector or such. And there is only one block cipher mode which won’t use initialization vectors, namely ECB. Every article on ECB says: “Old and busted, do not use!” We’ll later see proof that ECB is used by the newer file format as well.

Note: If initialization vectors were used, there would be another important thing to consider. Initialization vectors should never be reused, depending on the block cipher mode the results would be more or less disastrous. So something to check out would be: if I undo some changes by restoring a database from backup and make changes to it again, will the application choose the same initialization vector? This could be the case if the application went with a simple incremental counter for initialization vectors, indicating a broken encryption scheme.

Data authentication

It’s common consensus today that data shouldn’t merely be encrypted, it should be authenticated as well. It means that the application should be able to recognize encrypted data which has been tampered with and reject it. Lack of data authorization will make the application try to process manipulated data and might for example allow conclusions about the plaintext from its reaction. Given that there are multiple ideas of how to achieve authentication, it’s not surprising that developers often mess up here. That’s why modern block cipher modes such as GCM integrated this part into the regular encryption flow.

Note that even without data authentication you might see an application reject manipulated data. That’s because the last block is usually padded before encryption. After decryption the padding will be verified, if it is invalid the data is rejected. Padding doesn’t offer real protection however, in particular it won’t flag manipulation of any block but the last one.

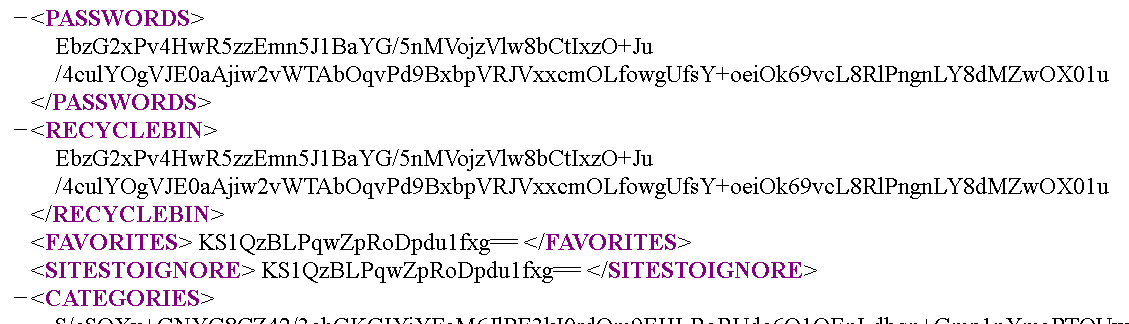

So how can we see whether Password Depot uses authenticated encryption? By changing a byte in the middle of the ciphertext of course! Since with ECB every 16 byte block is encrypted separately, changing a block in the middle won’t affect the last block where the padding is. When I try that with Password Depot, the file opens just fine and all the data is seemingly unaffected:

In addition to proving that no data authentication is implemented, that’s also a clear confirmation that ECB is being used. With ECB only one block is affected by the change, and it was probably some unimportant field – that’s why you cannot see any data corruption here. In fact, even changing the last byte doesn’t make the application reject the data, meaning that there are no padding checks either.

What about the encryption key?

As with so many products, the website of Password Depot stresses the fact that a 256 bit encryption key is used. That sounds pretty secure but leaves out one detail: where does this encryption key come from? While the application can accept an external encryption key file, it will normally take nothing but your master password to decrypt the database. So it can be assumed that the encryption key is usually derived from your master password. And your master password is most definitely not 256 bit strong.

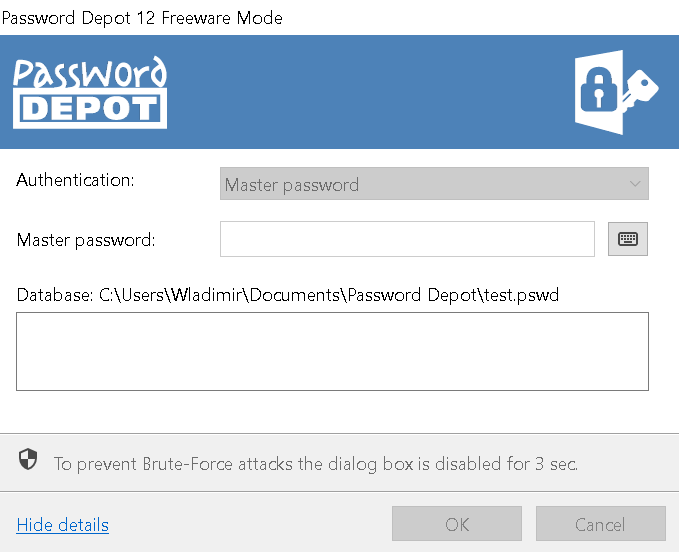

Now a weaker master password isn’t a big deal as long as the application came up with reasonable bruteforce protection. This way anybody trying to guess your password will be slowed down, and this kind of attack would take too much time. Password Depot developers indeed thought of something:

Wait, no… This is not reasonable bruteforce protection. It would make sense with a web service or some other system that the attackers don’t control. Here however, they could replace Password Depot by a build where this delay has been patched out. Or they could remove Password Depot from the equation completely and just let their password guessing tools run directly against the database file, which would be far more efficient anyway.

The proper way of doing this is using an algorithm to derive the password which is intentionally slow. The baseline for such algorithms is PBKDF2, with scrypt and Argon2 having the additional advantage of being memory-hard. Did Password Depot use any of these algorithms? I consider that highly unlikely, even though I don’t have any hard proof. See, Password Depot has a know-how article on bruteforce attacks on their website. Under “protection” this article mentions complex passwords as the solution. And then:

Another way to make brute-force attacks more difficult is to lengthen the time between two login attempts (after entering a password incorrectly).

So the bullshit protection outlined above is apparently considered “state of the art,” with the developers completely unaware of better approaches. This is additionally confirmed by the statement that attackers should be able to generate 2 billion keys per second, not something that would be possible with a good key derivation algorithm.

There is still one key derivation aspect here which we can see directly: key derivation should always depend on an individual salt, ideally a random value. This helps slow down attackers who manage to get their hands on many different password databases, the work performed bruteforcing one database won’t be reusable for the others. So, if Password Depot uses a salt to derive the encryption key, where is it stored? It cannot be stored anywhere outside the database because the database can be moved to another computer and will still work. And if you look at the database above, there isn’t a whole lot of fields which could be used as salt.

In fact, there is exactly one such field: <fingerprint>. It appears to be a random value which is unique for each database. Could it be the salt used here? Easy to test: let’s change it! Changing the value in the <fingerprint> field, my database still opens just fine. So: no salt. Bad database, bad…

Browser integration

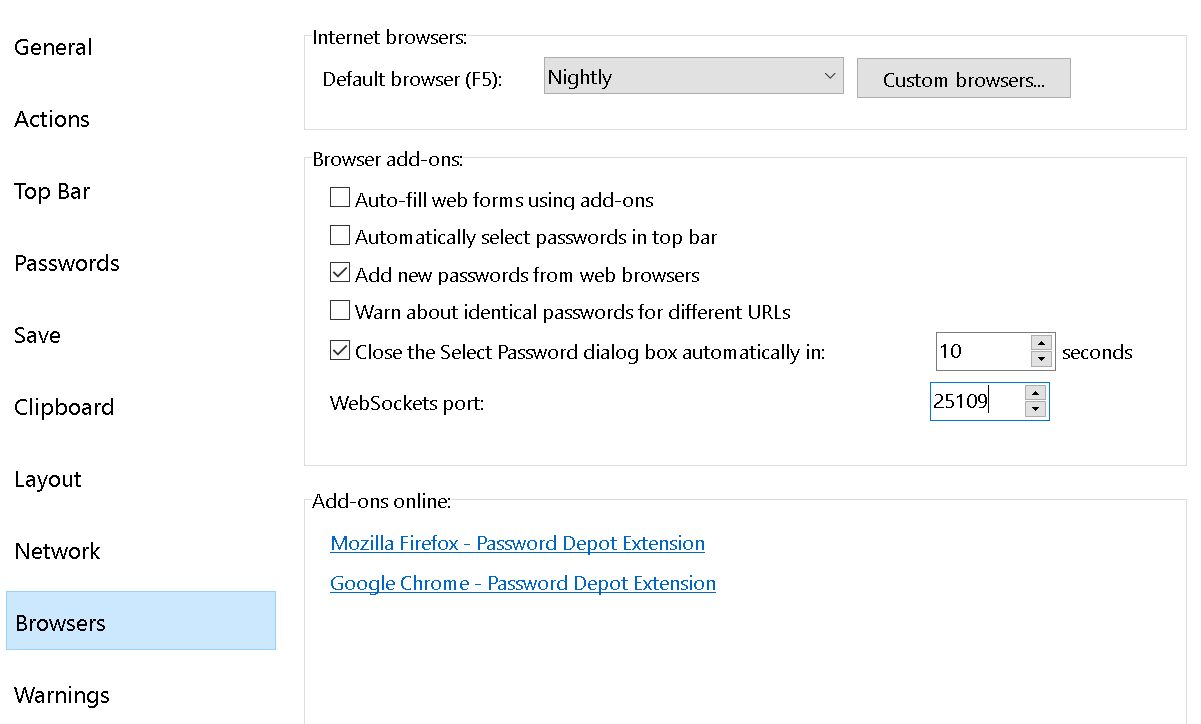

If you’ve been reading my blog, you already know that browser integration is a common weak point of password managers. Most of the issues are rather obscure and hard to recognize however. Not so in this case. If you look at the Password Depot options, you will see a panel called “Browser.” This one contains an option called “WebSockets port.”

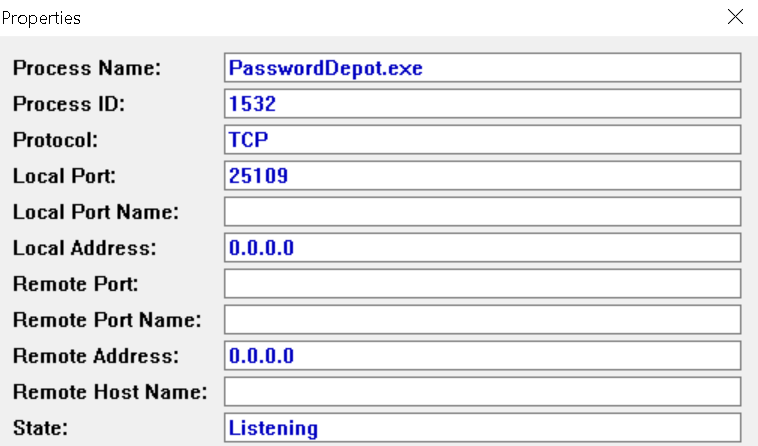

So when the Password Depot browser extension needs to talk to the Password Depot application, it will connect to this port and use the WebSockets protocol. If you check the TCP ports of the machine, you will indeed see Password Depot listening on port 25109. You can use netstat command line tool for that or the more convenient CurrPorts utility.

Note how this lists 0.0.0.0 as the address rather than the expected 127.0.0.1. This means that connections aren’t merely allowed from applications running on the same machine (such as your browser) but from anywhere on the internet. This is a completely unnecessary risk, but that’s really shadowed by the much bigger issue here.

Here is something you need to know about WebSockets first. Traditionally, when a website needed to access some resource, browsers would enforce the same-origin policy. So access would only be allowed for resources belonging to the same website. Later, browsers had to relax the same-origin policy and implement additional mechanisms in order to allow different websites to interact safely. Features conceived after that, such as WebSockets, weren’t bound by the same-origin policy at all and had more flexible access controls from the start.

The consequence: any website can access any WebSockets server, including local servers running on your machine. It is up to the server to validate the origin of the request and to allow or to deny it. If it doesn’t perform this validation, the browser won’t restrict anything on its own. That’s how Zoom and Logitech ended up with applications that could be manipulated by any website to name only some examples.

So let’s say your server is supposed to communicate with a particular browser extension and wants to check request origin. You will soon notice that there is no proper way of doing this. Not only are browser extension origins browser-dependent, at least in Firefox they are even random and change on every install! That’s why many solutions resort to somehow authenticating the browser extension towards the application with some kind of shared secret. Yet arriving on that shared secret in a way that a website cannot replicate isn’t trivial. That’s why I generally recommend staying away from WebSockets in browser extensions and using native messaging instead, a mechanism meant specifically for browser extensions and with all the security checks already built in.

But Password Depot, like so many others, chose to go with WebSockets. So how does their extension authenticate itself upon connecting to the server? Here is a shortened code excerpt:

var websocketMgr = {

_ws:null,

_connected:false,

_msgToSend:null,

initialize:function(msg){

if (!this._ws){

this._ws = new WebSocket(WS_HOST + ':' + options.socketPortNumber);

}

this._msgToSend = msg;

this._ws.onopen = ()=>this.onOpen();

}

onOpen:function() {

this._connected = true;

if (this._msgToSend) {

this.send(this._msgToSend);

}

},

send:function(message){

message.clientVersion = "V12";

if (this._connected && (this._ws.readyState == this._ws.OPEN)){

this._ws.send(JSON.stringify(message));

}

else {

this.initialize(message);

}

}You cannot see any authentication here? Me neither. But maybe there is some authentication info in the actual message? With several layers of indirection in the extension, the message format isn’t really obvious. So to verify the findings there is no way around connecting to the server ourselves and sending a message of our own. Here is what I’ve got:

let ws = new WebSocket("ws://127.0.0.1:25109");

ws.onopen = () =>

{

ws.send(JSON.stringify({clientVersion: "V12", cmd: "checkState"}));

};

ws.onmessage = event =>

{

console.log(JSON.parse(event.data));

}When this code is executed on any HTTP website (not HTTPS because an unencrypted WebSockets connection would be disallowed) you get the following response in the console:

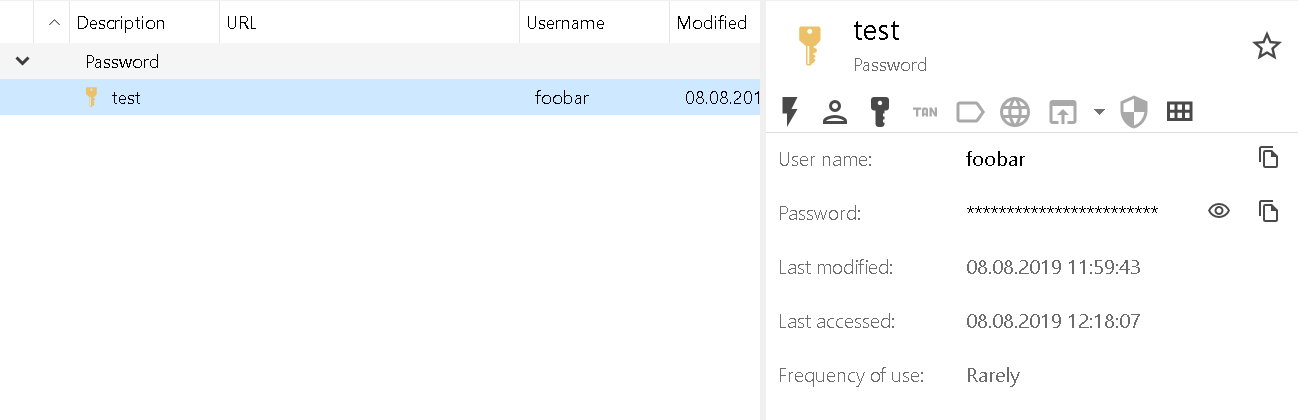

Object { cmd: “checkState”, state: “ready”, clientAlive: “1”, dbName: “test.pswd”, dialogTimeout: “10000”, clientVersion: “12.0.3” }

Yes, we are in! And judging by the code, with somewhat more effort we could request the stored passwords for any website. All we have to do for this is to ask nicely.

To add insult to injury, from the extension code it’s obvious that Password Depot can communicate via native messaging, with the insecure WebSockets-based implementation only kept for backwards compatibility. It’s impossible to disable this functionality in the application however, only changing the port number is supported. This is still true six months and four minor releases after I reported this issue.

More oddities

If you look at the data stored by Password Depot in the %APPDATA% directory, you will notice a file named pwdepot.appdata. It contains seemingly random binary data and has a size that is a multiple of 16 bytes. Could it be encrypted? And if it is, what could possibly be the encryption key?

The encryption key cannot be based on the master password set by the user because the password is bound to a database file, yet this file is shared across all of current user’s databases. The key could be stored somewhere, e.g. in the Windows registry or the application itself. But that would mean that the encryption here is merely obfuscation relying on the attacker being unable to find the key.

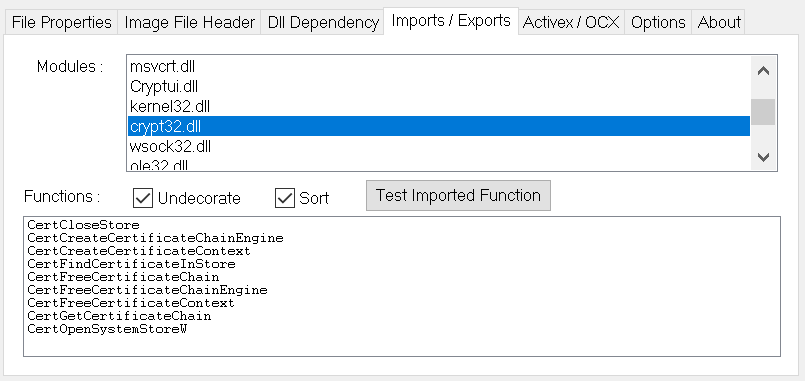

As far as I know, the only way this could make sense is by using Windows Data Protection API. It can encrypt data using a user-specific secret and thus protect it against other users when the user is logged off. So I would expect either CryptProtectData or the newer NCryptProtectSecret function to be used here. But looking through the imported functions of the application files in the Password Depot directory, there is no dependency on NCrypt.dll and only unrelated functions imported from Crypt32.dll.

So here we have a guess again, one that I managed to confirm when debugging a related application however: the encryption key is hardcoded in the Password Depot application in a more or less obfuscated way. Security through obscurity at its best.

Summary

Today you’ve hopefully seen that “encrypted” doesn’t automatically mean “secure.” Even if it is “military grade encryption” (common marketing speak for AES), block cipher mode matters as well, and using ECB is a huge red warning flag. Also, any modern application should authenticate its encrypted data, so that manipulated data results in an error rather than attempts to make sense of it somehow. Finally, an important question to ask is how the application arrives on an encryption key.

In addition to that, browser integration is something where most vendors make mistakes. In particular, a browser extension using WebSockets to communicate with the respective application is very hard to secure, and most vendors fail even when they try. There shouldn’t be open ports expecting connections from browser extensions, native messaging is the far more robust mechanism.

Comments

Thank you for this series of articles on password managers. They have all been very insightful and taught me more about security.

Why is storing data encrypted on the local drive important? For nearly all users the event of an attacker getting access to a user account is usually game over. Better ensure local drive encryption and then have a password manager that does not require a password every time I use it, full text search etc . ie a much better user interface.

For example: because data never stays on your local drive these days. People always have multiple devices that they work with, so even if your password manager has no sync functionality of it own they will move the database between devices. And they will totally email it to themselves or invent similarly adventurous methods.

The other issue is that people will often forget to lock their computer. A coworker changing desktop background may be funny, them casually opening up your entire passwords database - not so much. It's just that: passwords are very sensitive data, so they need this additional protection.

Really interesting article, So if I understand this correctly, you could implement a website that would be able to exfiltrate local passwords from this password manager if the browser integration is turned on? Would have been cool to see if it will actually return the full passwords on request, for example by using the browser dev tools to check what (unauthenticated) requests the extension is making, and replaying them.

Yes, you understand correctly - except that in this particular case it isn't even possible to turn browser integration off, as long as the app is running it is always vulnerable.

It would be indeed nice to use dev tools for that. Unfortunately, Firefox dev tools aren't up to the job yet. I seem to remember that Chrome added WebSockets inspection to its dev tools recently? This might work.