Avast used to collect the browsing history of their users without informing them and turn this data into profits via their Jumpshot subsidiary. After a public outcry and considerable pressure from browser vendors they decided to change their practices, so that only data of free antivirus users would be collected and only if these explicitly opt in. Throughout the entire debacle Avast maintained that the privacy impact wasn’t so wild because the data is “de-identified and aggregated,” so that Jumpshot clients never get to see personally identifiable information (PII).

The controversy around selling user data didn’t come up just now. Back in 2015 AVG (which was acquired by Avast later) changed their privacy policy in a way that allowed them to sell browser history data. At that time Graham Cluley predicted:

But let’s not kid ourselves. Advertisers aren’t interested in data which can’t help them target you. If they really didn’t feel it could help them identify potential customers then the data wouldn’t have any value, and they wouldn’t be interested in paying AVG to access it.

From what I’ve seen now, his statement was spot on and Avast’s data anonymization is nothing but a fig leaf.

Contents

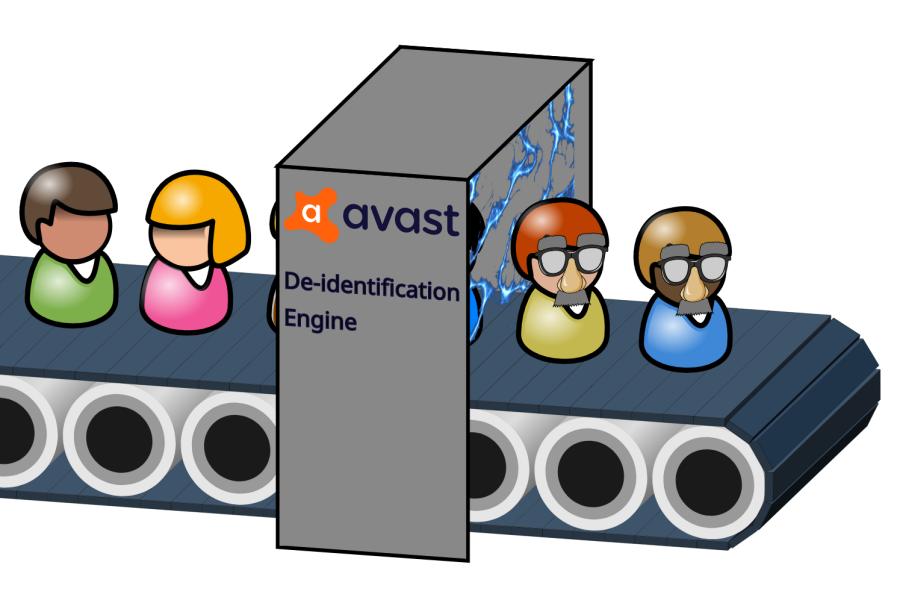

Overview of Avast’s “de-identification”

No technical details on the “de-identification” were shared, neither in Avast’s public statements, nor when they communicated with me and I asked about it. My initial conclusion was that the approach is considered a company secret, or maybe that it simply doesn’t exist. So imagine my surprise when I realized that the approach was actually well-documented and public. In fact, Avast Forum features a post on it written in 2015 by none other than the then-CTO Ondřej Vlček. There is an example showing how it works:

With a shopping site like Amazon, the URL before stripping contains some PII:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/buy/addressselect/handlers/edit-address.html?ie=UTF8&addressID=jirptvmsnlp&addressIdToBeDeleted=&enableDeliveryPreferences=1&from=&isBillingAddress=&numberOfDistinctItems=1&showBackBar=0&skipFooter=0&skipHeader=0&hasWorkingJavascript=1The algorithm automatically replaces the PII with the word REMOVED in order to protect our users’ privacy, like this:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/buy/addressselect/handlers/edit-address.html?ie=UTF8&addressID=REMOVED&addressIdToBeDeleted=&enableDeliveryPreferences=1&from=&isBillingAddress=&numberOfDistinctItems=1&showBackBar=0&skipFooter=0&skipHeader=0&hasWorkingJavascript=1

So when you edit your shipping address on Amazon, there will be a number of parameters in the page address collected by Avast. Only the addressID parameter is actually related to your identity however, so this one will be removed. But how does Avast know that addressID is the only problematic parameter here?

The patented data scrubbing approach

The forum post doesn’t document the decision process. Turns out however, there is US patent 2016 / 0203337 A1 filed by Jumpshot Inc. in January 2016. As it is the nature of all patents, their contents are publicly visible. This particular patent describes the methodology for removing private information from “clickstream data” (that’s Avast speak for your browsing history along with any context information they can get).

Most of the patent is trivial arrangements. It describes how Avast passes around browsing history data they receive from a multitude of users, even going as far as documenting parsing of web addresses. But the real essence of the patent is contained in merely a few sentences:

If there are many users which saw the same value of parameter, then it is safe to consider the value to be public. If a majority of values of a parameter are public, it is safe to conclude that parameter does not contain PII. On the other hand, if it is determined that a vast majority of values of a parameter are seen by very few users, it may be likely that that the parameter contains private information.

So if in their data a particular parameter typically has only values associated with a specific user (like addressID in the example above), that parameter is considered to carry personal information. Other parameters have values that are seen by many users (like hasWorkingJavascript in the example above), so the parameter is considered unproblematic and left unchanged. That looks like a feasible approach that will be able to scale with the size of the internet and adapt to changes automatically. And yet it doesn’t really solve the problem.

Side-note: How is their approach different from this patent filed by Amazon several years earlier that they actually cite? Beats me. I’m not a patent lawyer but I strongly suspect that they will lose this patent should there ever be a disagreement with Amazon.

How Amazon would deanonymize this data

The example used by Ondřej Vlček makes it very obvious who Avast tries to protect against. I mean, the address identifier they removed there is completely useless to me. Only Amazon, with access to their data, could turn that parameter value into user’s identity. So the concern is that Jumpshot customers (and Amazon could be one) owning large websites could cross-reference Jumpshot data with their own to deanonymize users. Their patent confirms this concern when explaining implicit private information.

But what if Amazon cannot see that addressID parameter any more? They can no longer determine directly which user the browsing history belongs to. But they could still check which users edited their address at this specific time. That’s probably going to be too many users at Amazon’s scale, so they will have to check which users edited their address at time X and then completed the purchase at time Z. That should be sufficient to identify a single user.

And if Jumpshot doesn’t expose request times to their clients or merely shows the dates without the exact times? Still, somebody like Amazon could for example take all the products viewed in a particular browser history and check it against their logs. Each individual product has been viewed by a large number of users, yet the combination of them is a sure way to identify a single user. Mission accomplished, anonymization failed.

How everybody else could deanonymize this data

Not everybody has access to the same amounts of data as Amazon or Google. Does this mean that in most scenarios Jumpshot data can be considered properly anonymized? Unfortunately not. Researchers already realized that social media contain huge amounts of publicly accessible data, which is why their deanonymization demonstrations such as this one focused on cross-referencing “anonymous” browsing histories with social media.

And if you think about it, it’s really not complicated. For example, if Avast were collecting my data, they would have received the web address https://twitter.com/pati_gallardo/status/1219582233805238272 which I visited at some point. This address contains no information about me, plenty of other people visited it as well, so it would have been passed on to Jumpshot clients unchanged. And these could retrieve the list of likes for the post. My Twitter account is one of the currently 179 who’s on that list.

Is that a concern? Not if it’s only one post. However, somebody could check all Twitter posts that I visited in a day for example, checking the list of likes for each of them, counting how often each user appears on these lists. I’m fairly certain that my account will be by far the most common one.

And that’s not the only possible approach of course. People usually get to a Twitter post because they follow either the post author or somebody who retweeted the post. The intersection of the extended follower groups should become pretty small for a bunch of Twitter posts already.

I merely used Twitter as an example here. In case of Facebook or Instagram the publicly available data would in most cases also suffice to identify the user that the browsing history belongs to. So – no, the browsing history data collected by Avast from their users and sold by Jumpshot is by no means anonymous.

What about aggregation?

But there is supposedly aggregation as well. In his forum post, Ondřej Vlček explicitly describes how data from all users is combined on per-domain and per-URL basis. He says:

To further protect our users‘ privacy, we only accept websites where we can observe at least 20 users.

And also:

These aggregated results are the only thing that Avast makes available to Jumpshot customers and end users.

This actually sounds good and could resolve the issues with the data anonymization. If it is true that is. On the now removed Jumpshot page advertising its “clickstream data” product it says:

Get ready to go deep. Dive in to understand the complete path to purchase, right down to individual products.

So at least some Jumpshot customers would get not only aggregated statistics but also the exact path through a website. Could that also be aggregated data? Yes, but it would require finding at least 20 users taking exactly the same path. It would mean that lots of data would have to be thrown away because users take an unusual path – the very data which could provide the insights advertised here. So while aggregated data here isn’t impossible, it’s also pretty unlikely.

A recent article published by PCMag also makes me suspect that the claims regarding aggregation aren’t entirely true. Their research indicates that some Jumpshot customers could access browser histories of individual users. Given everything else we know so far, I consider these claims credible.

Comments